School Choice Will Not Lead to Equity, Here’s Why

School Choice Will Not Lead to Equity, Here’s Why

School choice has been a hot topic for years and, given Mike Pence’s recent attack on Joe Biden for supposedly not supporting school choice, it is likely to be a key concept in the upcoming political debates on schooling and equity.

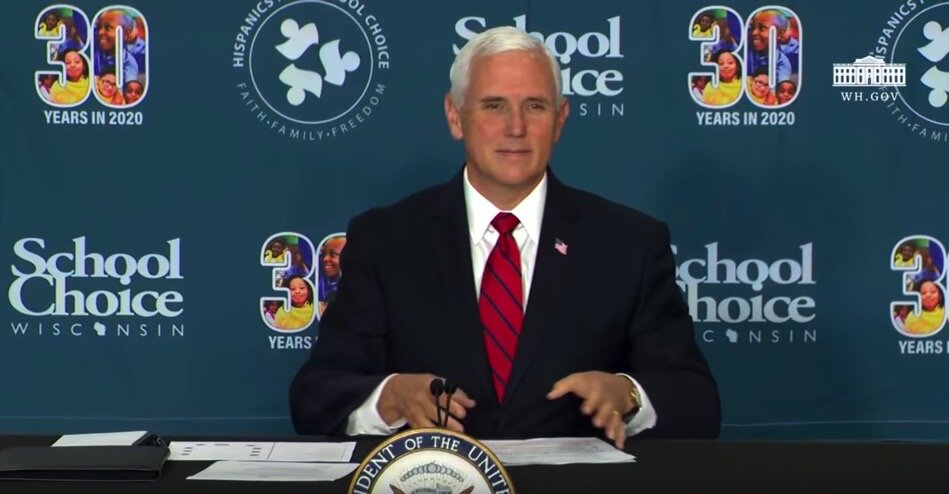

Pence presenting in June 2020 at a pro School Choice conference.

This administration under Betsy Devos’ Department of Education has doubled down on school choice. The basic argument is, if wealthy parents are able to choose their schools through where they purchase homes, wouldn’t it lead to more equitable outcomes if poor parents were given options to choose as well?

But don’t be fooled: using school choice to organize our schooling system will never lead to a more equitable system, and it will undermine our democracy in the process.

Here’s why.

School Choice Doesn’t “Work”

Perhaps the most salient point to start with is that “school choice” hasn’t actually worked to improve performance outcomes for most or all students involved. So, even if what you care about and measure is test scores, school choice doesn’t seem to work.

It has been 30 years since we began experimenting with charters and vouchers, the two main forms of choice in our schooling system. While there is some mixed evidence as measured by standardized tests, overall, vouchers have had no effect and charters have had little to no effect (and sometimes very negative effects — including increased racial and socio-economic segregation).

This should be enough, but there’s more (so, even if you disagree with my assertion that school choice doesn’t work to increase test scores, stick with me…). When we think more carefully about the logic and the framing of school choice it never should have been a debate in the first place.

School Choice is Driven by Poor Assumptions

The underlying logic of school choice from an economic model perspective is poorly conceived. The basic premise of the school choice argument is that a free market, driven by individual choice will result in competition that increases quality and efficiency by making producers a) improve their product to gain consumers (a.k.a. competition increases quality) and b) decrease their costs to improve profits (a.k.a competition increase efficiency — output:cost ratio).

There are economic, choice theory, and productivity arguments that undermine that this basic premise would work in a schooling “market.”

Poor assumption #1: Markets allow for good choice-making

Truth: Actually, without perfect information and good indicators of quality, markets can undermine good choice-making.

Basic economic theory requires that for these market models to work, participants need to have full information and be able to assess quality accurately in order to make a well-informed choice. Neither of these assumptions holds true in schooling markets: it is not clear that parents have access to full information to make the best choices, nor is quality as easily and accurately assessed as it might be when purchasing a consumer product or other service. Families don’t only care about test scores when they choose schools. Parents ask, “Will my child fit in? Will they have friends? Will teachers care about them? Can they do the activities they love?” — and they ask, “Will my child be safe? Will this school be convenient for our family?” — not just about test scores or indicators of culture more broadly.

Also, assuming markets facilitate good choice-making ignores the fact that in many marketplaces consumers are sold by marketing and emotional appeals rather than quality, which can also happen in the schooling market. Do we really want school budgets to increasingly go to marketing rather than the classroom?

So, choice does not necessarily lead to a better school for many children because it’s hard to make good choices when the data is limited and quality complex. And, making schools compete in a marketplace may lead to a distortion of the priorities of school by requiring more marketing as a proxy for quality, rather than actually increasing quality.

You could argue that these ‘market failures’ could be fixed by providing more/better information, but there’s more.

Poor assumption #2: More choice is better

Truth: Actually, more choice often leads to worse decision-making.

Choosing a school is a taxing and time-consuming process. Research on choice suggests that having too many choices can actually undermine rather than promote freedom and well-being — and make us more likely to choose incorrectly for our needs or abdicate the responsibility for choosing altogether.

School choice is most likely to benefit parents and families that have the time and resources to gather considerable information, and the savvy to figure out how to get their child enrolled in their chosen school. Students who are most vulnerable are least served by a choice model (e.g. those with parents working multiple low-wage jobs, who have trouble accessing or evaluating information, who speak a language other than English, or who simply don’t care enough to engage). This may be why charter systems have often resulted in more racial segregation and poverty concentration in schools.

When parents are overwhelmed by choices, or there is too much or too little information available, economic choice theory predicts they are less likely to choose well for their children’s needs.

Poor assumption #3: Competition will increase school quality and efficiency

Truth: Actually, competition in a complex environment is likely to lead to worse quality and no “efficiency” gains.

First, the idea that schools will increase quality because of competition rests on a primary faulty — and, frankly insulting — assumption that educators both know how to, and have the capacity to, make their schools better…but they just don’t because there isn’t any competition from other schools. Do we really think there’s some hidden bandwidth or knowledge in schools that isn’t being used just because educators aren’t in competition?

But furthermore, the idea that competition increases productivity or quality in complex environments isn’t even supported theoretically. Behavioral economics and social psychology suggest that complex activities are not as well-suited to competition-driven increases in productivity; in fact, competition is likely to decrease creativity, collaboration, efficiency, and effectiveness when the task is not clear and simple or when the goal is framed as a win:lose situation (like when funding is tied to ‘winning’ students). Even for consumer goods, complex activities and complex markets require collaboration and cooperation, not just competition and schools are not assembly lines creating widgets, or companies offering a product. Classrooms are complex social environments responsible for the complex development of our children.

Even the idea of “efficiency” is a more complicated topic in education than in traditional business models. So, what does it mean to be an “efficient” school? Efficiency in a typical business scenario means lowering costs to increase profits. For schooling “efficiency” the proxy for profit is “test scores” or an achievement variable like “graduation rates” — so, in other words, efficiency in schooling is often defined as spending less money for similar increases in test scores.

But what does that actually mean? Let’s explore. Education is a necessarily a human capital-intensive industry, which means the largest line item in the budget is human capital: aka teachers’ compensation. There are three main ways you can decrease the ratio of teacher compensation to overall budget: 1) hire younger or less experienced teachers (as many charter networks do); 2) cut teacher pay (despite the fact that teachers across the country already make less, on average, than similarly well-educated peers in other industries); or, 3) increase the student:teacher ratio (i.e. number of students taught by each teacher).

A school might be able to maintain or even increase test scores using any of these three tactics but would we actually say any of these are better or more “efficient” at achieving the outcomes we want for our society from a big picture perspective? Even if test scores go up…Do we actually think students’ experience is better when most teachers are inexperienced? Do we think students are better served when their teachers are stressed by money issues, or have to work multiple jobs? Do we think we, as a society, are better when teachers, who make up ~2% of the U.S. workforce, are not earning enough to be comfortably in the middle class? Are test scores really what we care most about anyway?

[[As a side note, the efficiency argument becomes even more complicated when you consider for-profit schools receiving public money: for-profit schools become more “efficient” by taking pay away from teachers and transferring it to stockholders or owners. For-profit charters basically take public money and transfer it to a wealthy few rather than paying it to teachers for their work.]]

School Choice Changes Education from the Right of a Citizen to the Choice of a Consumer

Okay, pause.

These are all valid reasons for questioning the choice paradigm and should be brought into discussions about school choice. Each can be debated theoretically and tested empirically.

However, I am going to now intentionally leave those debates behind as I want to explore the assumptions that lie underneath the choice argument about the purpose and aims of schooling. The entire debate is moot and has been leading us down the wrong road for decades.

School choice is not something we should be debating if we want to maintain a democratic society. School choice takes an inherently public good and frames it as a private good — and we all lose because of it.

From an economics perspective, schooling as a public good simply means that, as a society, we all are better off if other people’s children are more educated — and, it is likely that many individuals would under-invest in their own children’s education relative to the societal benefit we gain from those children being educated. This is because educated children grow up to have or create good jobs, to be more-informed citizens, and to adhere more closely to public norms and laws. Considerable research finds that the more educated a country is, the higher its GDP per capita and returns to education are around found to be about 10%.

But perhaps a political science or sociology perspective, not economics, is more useful here. For individuals, education is a human right, not a private good. Furthermore, schooling is not just for individuals — it also has a collective purpose: to socialize students into a complex democracy and create sites where local citizens practice deliberative democracy in the running of their schools for the good of all of their children.

In other words, it doesn’t matter if choice “works” or not to increase test scores or achievement: it’s a sleight-of-hand trick to frame the debate here. This debate makes everyone put energy into “proving” that traditional public schools are better at the local level than charter schools when that’s really beside the point. While any particular charter school might be high quality or low quality for the students involved, just as any traditional public school might be high quality or low quality — from a systems perspective, introducing the need for choice undermines our democracy.

Framing equity as school choice shifts how we think about who is responsible for ensuring each child receives a good education, how it’s funded, where schools are located, and what outcomes are desired.

Fundamentally, arguing choice is the way to equity assumes that the purpose of schooling is to prepare individuals to maximize their own development and opportunity in the socioeconomic system, thus individuals should be allowed to navigate the education “marketplace” so that it best serves their own instrumental interests.

In other words, school choice assumes an individual efficiency purpose for schooling (i.e. the purpose of school is to ensure every individual can maximize their personal achievement in the system). Sometimes this is hidden in an individual possibility language (i.e. individual kids will learn more if they can choose the best school for them); however, fundamentally it’s about achievement and efficiency.

When schooling becomes privatized and part of the market, social and cultural concerns become much less important, unless they can also be seen as part of the market system. When education is seen as largely in the public rather than private interest, we’re less likely to get so fixated on test scores — it is more likely to be seen as having a range of social and cultural objectives, along with the economic.

The same is true but often ignored in other markets. Consumer choices in products don’t often take into account the full range of impact a product has on society as a whole — we continue to purchase cars and plastics that have huge environmental consequences, for instance, and to allow corporations to make decisions that exacerbate climate change.

However, in the case of schooling, the effects are more immediate on the social fabric: if the socialization, national unity, and democratic values are not considered in the design of our system and the management of our schools they are unlikely to be pursued and at great cost to society.

Furthermore, when we frame school as a private good we shift the onus from being on governments to provide good education for all of its citizens, to being on individuals being savvy enough to choose.

And, if you don’t choose well? That’s on you, not on us. You (/your children) deserve whatever life outcomes result. If schooling ends up more racially and income segregated? Well, not on us — that’s what parents are choosing.

But, true educational equity is not achieved when every child can compete within an unequal system — where they have an equal opportunity to end up in a few spaces on the top. True educational equity is achieved when every child develops the knowledge, skills, character, and beliefs they need to reflect accurately on their world, make choices aligned with their values and preferences, and work with others through democratic processes to make the whole system more equal and equitable for all.

Equity as choice says that every consumer should be able to choose what’s best for them to “race to the top”, but equity as a citizen means you shouldn’t be burdened with having to choose — you have a right to a good school, in your neighborhood, provided by your government, and run together locally.

Education should be a right of citizens, not a choice of consumers. The school choice debate makes schooling into a private good when it should be a public good. We should invest to make every school great, not promote the right to choose.